Executive Summary:

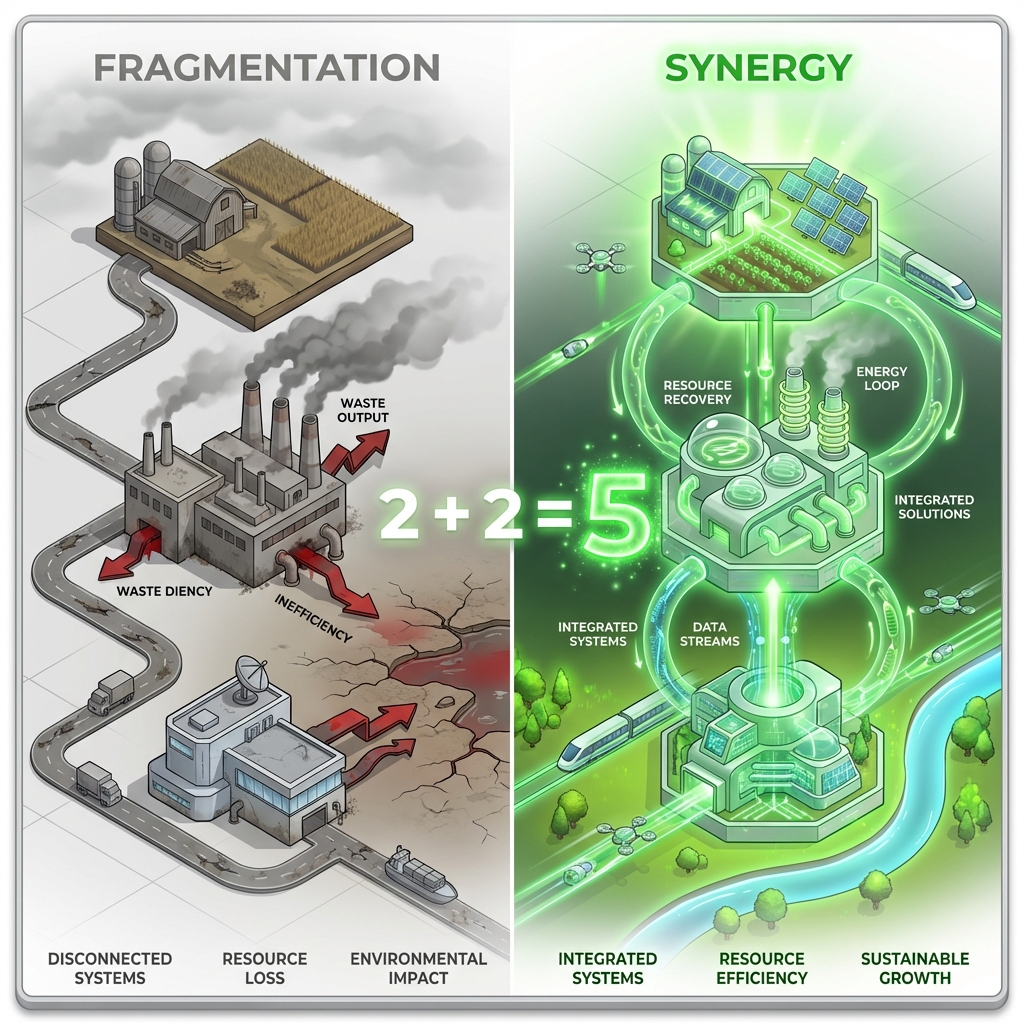

A Hemphub is not a rigid franchise; it is an adaptable industrial node. While the core principle of synergistic processing remains constant, the physical implementation shifts based on geography. In this article, we analyze three distinct archetypes defined in the Hemphub Infrastructure Strategy: the high-volume Fiber Model (Northern Europe), the high-margin Cannabinoid Model (North America), and the nutritional Food Model (Asia-Pacific). Understanding these variations is critical for investors and developers to match infrastructure with local agronomic reality.

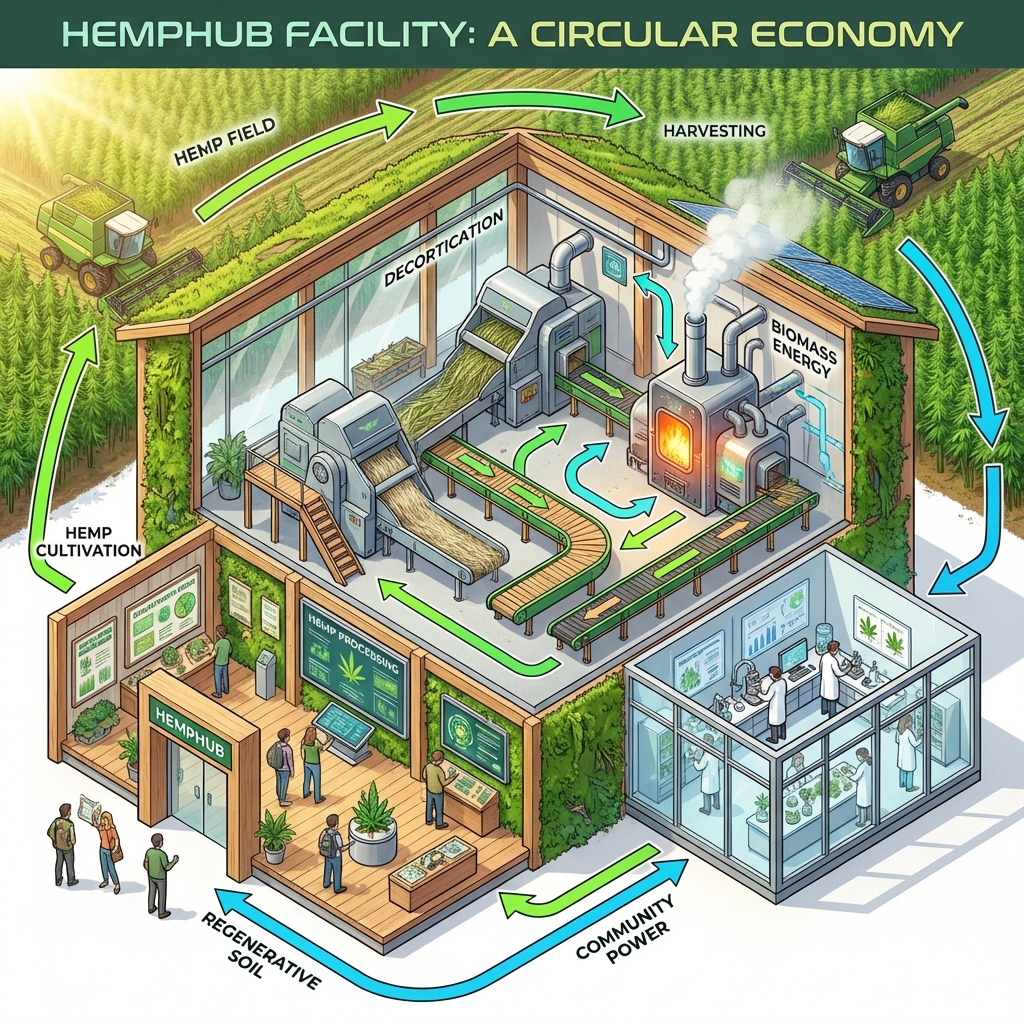

Over the last few days, we’ve defined the Hemphub as a universal concept: a regenerative combined-cycle node. However, the application of this concept is not rigid. A Hemphub in the snowy plains of Northern Europe looks very different from one in the sun-drenched valleys of Colorado or the agricultural terraces of Asia.

Drawing from Section VI of the Hemphub Infrastructure Strategy, today we explore the three distinct „Archetypes” of the Hemphub. These models demonstrate how the infrastructure adapts to local geography, market demands, and agronomic conditions while maintaining the core principle of synergistic processing.

1. The Fiber-Focused Hemphub (Northern European Model)

Ideal Location: Rural France, Netherlands, or Baltics.

Primary Zone: 2,000 hectares cultivation radius.

This archetype is the heavy lifter of the bioeconomy. Built in regions with strong industrial traditions and construction demands, its „North Star” is biomass volume.

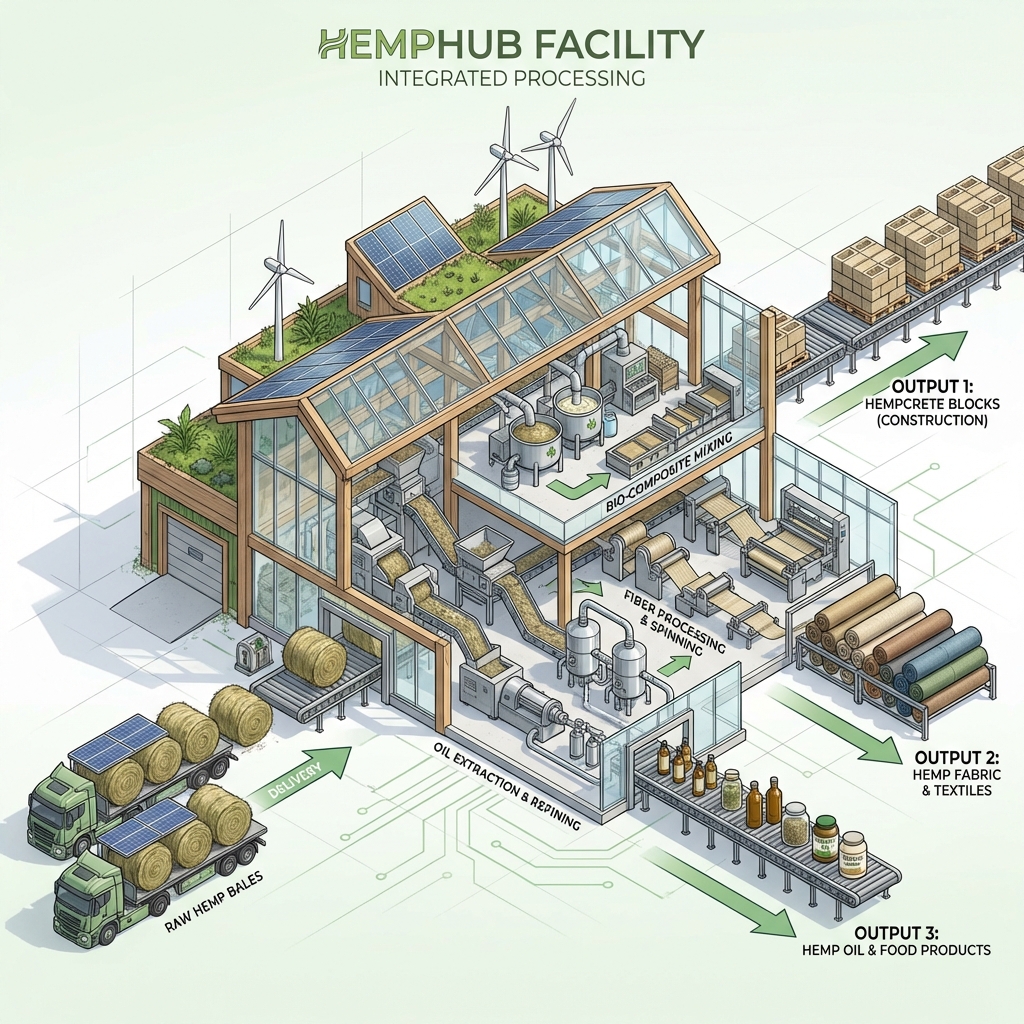

- The Engine: Large-scale decortication lines capable of processing massive tonnage of stalks.

- The Output: High-performance technical textiles for the automotive industry and hempcrete binders for green building.

- The Synergy: While fiber is the main driver, the „dust” and shives are not wasted—they power the facility’s own heating systems or are pelletized for local energy, ensuring a closed-loop energy cycle.

- Economic Profile: High volume, stable margins. Revenue projected at €12-18M annually.

2. The Cannabinoid-Focused Hemphub (North American Model)

Ideal Location: Oregon, Colorado, or Southern Europe.

Primary Zone: 500 hectares cultivation radius.

In regions where legislation permits and wellness markets are mature, this model pursues high-value extraction. It is smaller in land area but more capital-intensive in technology.

- The Engine: cGMP-compliant supercritical $CO_2$ or ethanol extraction laboratories.

- The Output: Pharmaceutical-grade CBD, CBG, and minor cannabinoids for wellness and medical applications.

- The Synergy: Unlike the „boutique” growers of the past who threw away the stalk, this Hemphub captures the fiber and hurd as valuable co-products, selling them to nearby construction or textile hubs. It turns a „waste disposal cost” into a secondary revenue stream.

- Economic Profile: Lower volume, high margin. Revenue projected at $15-25M annually.

3. The Food & Wellness Hemphub (Asia-Pacific Model)

Ideal Location: Australia, New Zealand, or China.

Primary Zone: 1,500 hectares cultivation radius.

Focusing on the „Superfood” revolution, this archetype prioritizes the seed.

- The Engine: Cold-pressing facilities for oil and dehulling lines for hearts.

- The Output: Omega-rich hemp seed oil, protein powders, hemp milk, and cosmetic bases for export.

- The Synergy: The residual seed cake (after pressing) is not discarded but upcycled into animal feed or high-protein flour. The stalks are baled and sent to regional biocomposite manufacturers, ensuring that the „food crop” still supports the „industrial crop” ecosystem.

- Economic Profile: Balanced volume and margin. Revenue projected at AUD $10-16M annually.

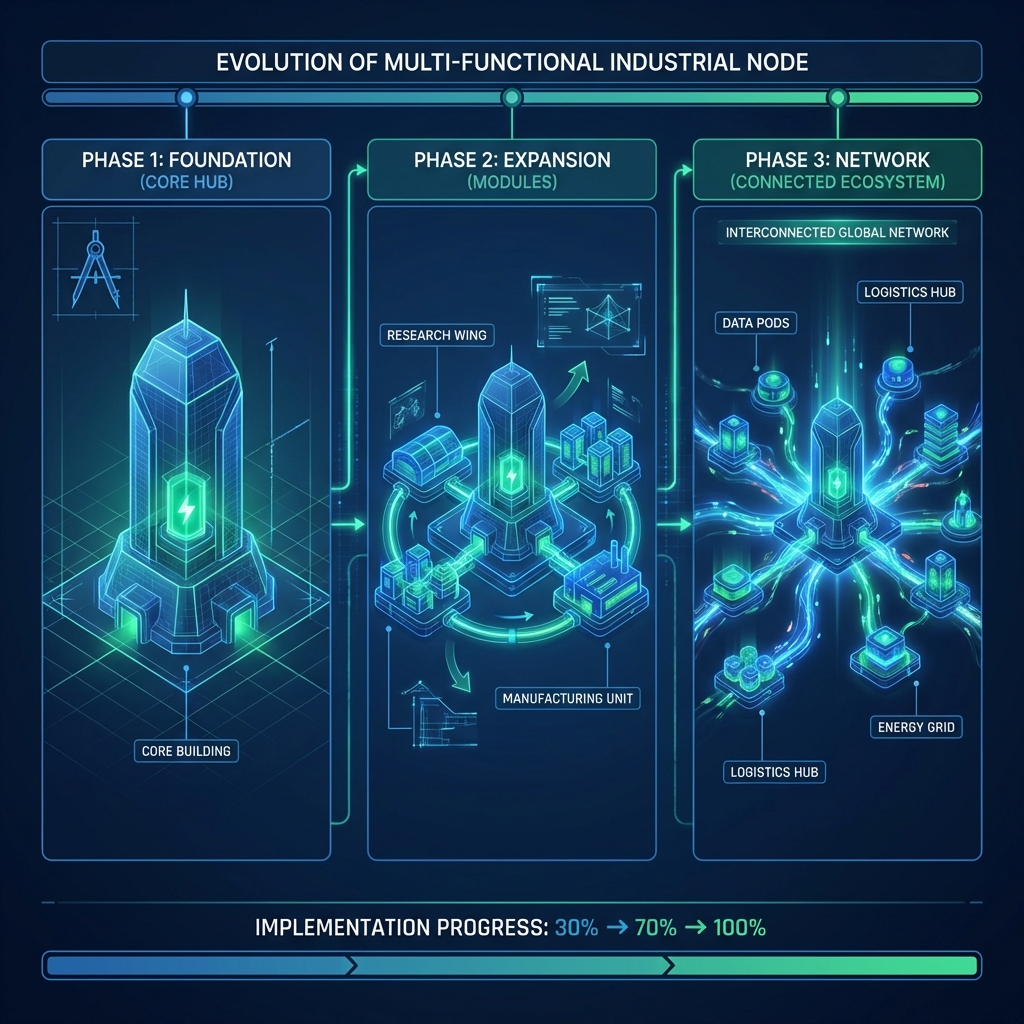

The Chameleon Infrastructure

What makes the Hemphub strategy powerful is this adaptability. It is not a rigid franchise model but a modular framework. A region can start as a Fiber Hub and, as legislation changes, add a Cannabinoid extraction module (as detailed in our Rollout Strategy).

The Hemphub is a chameleon—it takes on the color of its local economy while growing the same green future.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q: Can a single Hemphub be all three types at once?

A: Eventually, yes. However, specialized starts are recommended to manage initial CapEx ($5-20M). Most hubs begin with one primary focus (Fiber, Food, or Flower) and add modules in Years 3-5.

Q: Why does the Fiber model require so much more land (2,000 ha)?

A: Fiber is a high-volume, lower-margin commodity compared to CBD. To achieve the 24/7 distinct throughput required for profitability, a fiber decortication plant needs distinct tonnage that only a larger acreage can provide.

Q: Are these revenue projects guaranteed?

A: No. These are estimated modeled ranges based on current market prices for varied outputs. Actual performance depends on crop yield, operational efficiency, and local market uptake.

Topical Authority Note:

This content is based on Section VI of the Hemphub Infrastructure Strategy. Analysis performed by [Antigravity Agent] verified against the primary thesis document.

Tomorrow: We conclude our series on the Hemphub Infrastructure. We will layout the Stakeholder Call to Action—what you (investors, policymakers, farmers, and citizens) can do to bring this vision to life. Join us for Day 52: The Call to Action.

Source: The Synergistic Imperative And The Hemphub Infrastructure

Image Generation Prompt:

Prompt: A split-screen triptych architectural visualization showing three distinct variations of the „Hemphub” industrial facility adapted to different environments. Left panel: „Fiber Hub” in a snowy, flat Northern European landscape with piles of raw stalks. Center panel: „Pharma Hub” in a sunny, arid North American region with high-tech glass greenhouses. Right panel: „Food Hub” in a lush, green Asia-Pacific terrace setting. All three share a common futuristic, sustainable design language (wood, glass, greenery) but differ in scale and surrounding biome. High detail, photorealistic, 8k.